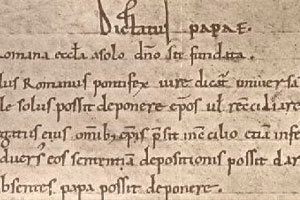

The pontificate of Saint Gregory VII (1073-1085) (born Hildebrand of Soana) constitutes one of the high points of the Christian Middle Ages. The pinnacle of his pontificate is the Dictatus Papae, a collection of twenty-seven statements defining the pope’s prerogatives and his relationship with temporal authority.

In it, Gregory proclaimed the pontiff’s superiority over the emperor in religious and moral matters. He asserted for the Papacy the role of the highest and most preeminent power on earth. This work was likely written between 1075 and 1078, at the height of the bitter conflict with the German ruler Henry IV. At the time, Henry was not yet Holy Roman Emperor. Nonetheless, he had already initiated the so-called investiture controversy against the Church.

“The Roman Pontiff,” affirms St. Gregory VII, “is rightly called universal.” (n. 2); “his title is unique in the world” (n. 11); “no one can reform any statement he issues; conversely, he can reform any statement issued by anyone else.” (n. 18); “no one can judge him” (n. 19); “the Roman Church has never erred nor will it ever err for all eternity, according to the testimony of the Scriptures” (n. 22); furthermore, “it is licit for the pope to depose emperors” (n. 12) and “he can release subjects from fidelity to the wicked” (n. 27).

Theologically, by appealing to his role as universal pastor, Gregory rejects the assertion that the papal throne cannot excommunicate kings or release their subjects from their bonds of fealty. The doctrine of Saint Gregory VII is based on the words with which Our Lord invested Saint Peter—the power to bind and loose both on earth and in Heaven—and on various passages from Gregory the Great and other writers. He questioned how it could be possible to maintain that he who has the power to open and close the gates of Heaven does not have the power to judge the things of this world. According to Gregory, Peter was constituted sovereign over the world’s kingdoms. To him, God subjected all the principalities and powers of the earth, granting him the power to bind and loose in Heaven and on earth. Kings and emperors are not exempt from those divine and natural laws to which all men are subject and the Church is the guardian.

Help Remove Jesus Bath Mat on Amazon

During the synod of February 1076, consistent with these claims, Gregory VII dismissed and excommunicated the German King Henry IV. In the process, Gregory also exempted Henry’s subjects from their oath of fealty. Henry’s excommunication and deposition were renewed at the Roman Synod of 1080, when Gregory confirmed the election of Rudolph of Swabia as Emperor.

In 1119, the Archbishop of Vienna, Guy of Burgundy, was elected Pope at Cluny, taking the name Callixtus II (1119-1124). He invoked the teachings of Gregory VII. On October 29-30 of the same year, a great synod took place in Reims in the presence of more than 400 bishops. There, the pope renewed the condemnation of Emperor Henry V, son of Henry IV. As the pope pronounced the words of excommunication, the four hundred bishops broke the candles they held. Later, the Concordat of Worms (1122) ended the investiture controversy. It recognized the Church’s direct universal supremacy on the spiritual plane and its indirect power on the temporal plane. Callixtus II then held the Ninth Ecumenical Council in the Lateran in March 1123. It was also the first assembly of all bishops held in the West. At it, the new agreement between the Church and the Empire was solemnly confirmed.

Satanic Christ Porn-blasphemy at Walmart — Sign Petition

The eighth statement of the Dictatus Papae, according to which “Only the pope can use the imperial insignia,” has sparked controversy throughout the centuries. Yet this statement encapsulates the entire political theology of the Middle Ages. The Church is not only the supreme spiritual authority but also the source of imperial authority. The Church possesses two means of coercion. The first is spiritual, ecclesiastical censures. The second is material, the right to vis armata. This constitutes the juridical-canonical foundation of the Crusades, as proclaimed by the Roman Pontiffs in the name of this authority. This thesis was later enunciated, among others, by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux when, in the treatise De consideratione, he reminds Pope Eugene III that both swords—the spiritual and the material—belong to the pope and the Church. This relationship is depicted in the art of the period. The pope is always depicted at the top, and the emperor stands one step below to his left. Below the emperor are all the kings and sovereigns of the temporal sphere. Then, gradually, the artist depicts all members of the Catholic hierarchy who govern the spiritual sphere.

The power of excommunication and deposition of sovereigns, which transcends the Middle Ages, stems from this doctrine. In 1535, Pope Paul III declared King Henry VIII of England deprived of his kingdom. On February 25, 1570, Saint Pius V issued a declaration against Queen Elizabeth Tudor in which, in the name of the powers conferred upon him, he declared her guilty of heresy. She was subsequently excommunicated and deprived of her supposed right to the English crown. No oath of fidelity bound her subjects to her any longer. Indeed, , they were forbidden to obey her under penalty of excommunication.

How Panera’s Socialist Bread Ruined Company

In the fifth book on De Romano Pontifice, Saint Robert Bellarmine explains that divine right does not give the pope direct temporal jurisdiction. He does, however, possess extensive indirect jurisdiction. The Jesuit Doctor also bases this conclusion on the Dictatus Papae of Saint Gregory VII. Two eminent twentieth-century jurists, Father Luigi Cappello and Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, considered this to be the position of the Magisterium of the Church as described in their manuals of Ecclesiastical Public Law, which educated the clergy until recent times. Cardinal Alfonso Maria Stickler also confirmed it in his studies on the history of canon law. The power to excommunicate and depose a prince derives from the plenitudo potestatis of the Church, founded on its power to loose and bind.

Gregory VII’s Dictatus Papae, like other famous documents such as Boniface VIII’s bull Unam Sanctam and Pius IX’s Syllabus, is an essential text for understanding the Church’s thinking on the relationship between the spiritual and temporal orders.

Saint Gregory VII gave his name to the most profound reform of the Church in the Middle Ages. His was a genuine spiritual and moral reform, also founded on the fullness of power of the Vicar of Christ, the plenitudo potestatis. Gregory VII would have liked to complete his spiritual reform by calling a grand crusade against the infidels. However, that task fell to his successor (one of his disciples), Blessed Urban II, a Cluniac Benedictine, who had the honor of proclaiming it. The epic of the Crusades was born from the spirit of Gregorian and Cluniac reform to the cry of “God wills it.” That most illustrious chapter of the Church’s history took place between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries.

First published on TFP.org.