In his book, Return to Order, author John Horvat described a spirit of unrestraint that dominated culture and economy, which he called frenetic intemperance. The following article is part of a series of articles written by history teacher Edwin Benson that explains some stages by which America adopted this spirit of frenetic intemperance and its consequence in society. This article deals with the making of the American consumer, especially with the introduction of the installment plan.

Human beings make economic decisions constantly. Where do we live? What do we do for a living? What time do we awaken? What do we drive? What do we eat? Where do we visit? What are our leisure time activities? What television shows (if any) do we watch? Do we scan through the commercials, watch them, or get up to make a sandwich? All of these, and literally hundreds of other times each day, we make decisions motivated–at least in part–by economics.

With that in mind, it should surprise no one that a fertile ground for frenetic intemperance is the economic structure of our daily lives.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a massive change was beginning to take place in the economic life of the average American. Prior to 1920, the majority of Americans lived in areas designated by the Census Department to be rural.[1] Of those, it is safe to say that the vast majority made their living in some sort of agriculture.[2]

That single change to more urban living created several other changes. One of the most significant changes was the fact that most Americans by 1920 had a regular income that could be largely determined in advance. To say that a farmer’s income was uncertain is an exercise in understatement. Weather and economic conditions, far beyond the farmer’s control, could make any given year one of prosperity or disaster. In comparison, the wages of a factory worker were relatively reliable. They were set in advance, and actual payment was made on a weekly, bi-weekly or monthly basis. Under normal circumstances, the wage laborer could determine monthly income with a fair degree of accuracy.

This, in turn, caused a massive change in the way that income was spent. Even in a good year, the farmer needed to save whatever amount was possible because next year could be worse. The city dweller was far more likely to spend income in excess of needs because of the ability to count on more coming in the future. Sometimes, of course, a disaster could change that picture–but it usually did not.

This change happened gradually. Those raised with a rural sense of thrift were slow to abandon the teachings of childhood, even if they did migrate to some city or town. However, the temptations were many. The well-thumbed Sears, Roebuck Catalogue–itself a revolution in retailing–gave way to department stores where products could be seen, touched, and compared to other similar products. Electricity, indoor plumbing, and central heat, unavailable on most turn of the century farms, were commonplace in cities. The automobile offered both farmers and wage-earners mobility beyond their childhood dreams.

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

Still, the temperate habits of childhood died hard.

To motivate people to buy, another retailing revolution would need to take place. The unlikely revolutionary was the president of General Motors, Alfred P. Sloan. Sloan wanted to sell more Chevrolets and displace Ford as the dominant American low-priced car. However, by 1919, Ford had cut his manufacturing costs to the bone and could sell the Model T for less than $525, while the comparable Chevrolet sold for $735.[3] Also, the multi-millionaire Ford owned all the stock in his company and cared little about profits. Sloan knew that GM’s stockholders cared very much about profits. He also knew that he could not cut costs below Ford’s level. The Chevrolet was more attractive and more powerful than the Ford, but that strategy alone was not convincing enough people to spend the extra money.

That year Sloan came up with a solution that changed the face of American retailing. To purchase the Ford, you needed to pay cash on the barrelhead. In a country where five dollars a day was a generous wage for a factory worker, that was a tall order. Sloan would sell you the Chevrolet for $50.00 down and $20.00 a month. Now the thriftier Ford buyer looked like a skinflint while the man making payments on the Chevy appeared to be the better husband and family provider.

Sloan called his innovation “buying out of income” but it came to be more generally known as the Installment Plan. Still, it took some work to convince many Americans that debt was a good thing. According to a GM publication from the mid-1920s, “Rent, heat, light, food, are essential commodities used by the family and are paid for out of current income. … Transportation by motor car is an essential commodity used by the family and is properly purchasable out of current income because the car represents an asset of continuing value.”[4]

It spread faster than the advent of sliced bread. By 1925, GMAC–as the new financing arm was called–had financed over 1,308,000 cars and trucks.[5] By that time, refrigerators, stoves, rugs, furniture, jewelry, radios, and even the house itself could be purchased for a series of “small monthly payments.” This gave rise to a frenzy of new buying just beyond one’s income.

Every new payment made daily life easier. The refrigerator was so much more convenient than wrestling with 50-pound blocks of ice. No one had to get up two hours before breakfast to build a fire in a stove that was hooked up to gas. The worn out dining set of early marriage could be discarded in favor of new furniture that could seat the whole family when they come over for Thanksgiving. Momma got the wedding ring that she had always deserved. Money previously spent on movies could be saved because the family stayed home to listen to Jack Benny on the radio. With each purchase, it became easier to justify the next.

Every new payment made daily life easier. The refrigerator was so much more convenient than wrestling with 50-pound blocks of ice. No one had to get up two hours before breakfast to build a fire in a stove that was hooked up to gas. The worn out dining set of early marriage could be discarded in favor of new furniture that could seat the whole family when they come over for Thanksgiving. Momma got the wedding ring that she had always deserved. Money previously spent on movies could be saved because the family stayed home to listen to Jack Benny on the radio. With each purchase, it became easier to justify the next.

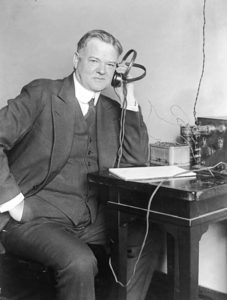

With all that buying going on, the economy boomed. America had entered a “new era.” Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover said that there would be no more poverty.[6] Questioning the health of the economy became positively unpatriotic. Purchasing created jobs, at least for a while.

Of course, neither Herbert Hoover nor John Q. Public knew what was coming next.

________________________________

[1] https://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/files/urpop0090.txt

[2] For instance, in 1900 there were 5,739,657 farms serving a population of 76,212,168 or one farm for every 13.3 people in the US. In the most recent census (2010) the US had a population of 308,745,538 being served by 2,201,000 farms or one farm for every 140.2 people.

[3] http://modelt.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11:original-model-t-ford-prices-by-model-and-year&catid=5:history-and-lore&Itemid=1, “Hand Book of Automobiles 1919”, National Automobile Chamber of Commerce, page 116.

[4] “Before You Buy Another Car”, GM publication, no date (c. 1925).

[5] Ibid.

[6] “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land. The poorhouse is vanishing from among us. We have not yet reached the goal, but given a chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years, and we shall soon, with the help of God, be within sight of the day when poverty shall be banished from this nation.” – Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover accepting the Republican nomination for the presidency, August 11, 1928.