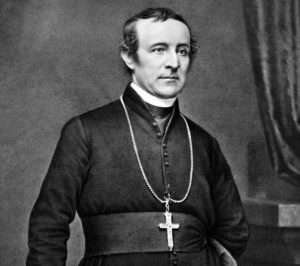

If there are “rags to riches” stories in the Church, surely the story of John Joseph Hughes is one of them. He is one of the most inspiring figures from the history of American Catholicism.

If there are “rags to riches” stories in the Church, surely the story of John Joseph Hughes is one of them. He is one of the most inspiring figures from the history of American Catholicism.

If you have ever stepped into the vastness of St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue in New York City, you have experienced a small piece of the legacy of Archbishop Hughes. He also built the Catholic parochial school system in New York, which inspired systems in other dioceses throughout the nation. He founded Fordham University. He oversaw the construction of many parishes to meet the spiritual needs of immigrants, especially the overwhelming number of Irish immigrants who flooded into New York during the Irish potato famine.

Under three different titles1, he ran what was to become the New York Archdiocese from 1837 until his death in 1864. In a nation that was permeated with Anti-Catholicism, he was consulted by four presidents (Fillmore, Polk, Buchanan, and Lincoln), and became the close friend of President Buchanan.

However, those achievements – great as they are – do not make Archbishop Hughes a ‘representative character’ of the sort mentioned in John Horvat’s Return to Order. In that book, the author writes of the need for outstanding figures that take the principles, moral qualities, and virtues found in their communities and translate them into concrete programs of life and culture. By their virtue and discernment, these characters draw and fuse society together to formulate communities rich in purpose and culture.

A PRODUCT OF HIS CULTURE

One characteristic of representative characters is that they “are as much a product of their society as their own efforts.”2

John Hughes was not only helped the U.S. absorb nearly two million Irish immigrants, he was an Irish immigrant himself. Patrick and Margaret Hughes were tenant farmers in County Tyrone. Marginally well off at first, they sent the brightest of their many children to school. Financial reverses forced John to leave school to help on the failing farm. From 1816-1819, the family immigrated in stages to the United States, eventually ending up on a farm near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

Archbishop Hughes could speak for the Irish immigrant, because he had experienced in the 1810’s what so many of them were experiencing twenty-five years later. His father never adjusted to life in America and died broken in spirit. His mother cared for a large family with barely enough to get by. However, John Hughes also knew what America had to offer, as he saw his brothers build prosperous farms and his sisters marry respectable men.

What Does Saint Thomas Say About Immigration?

The Archbishop was representative in another context. He represented the Catholic Church to the United States. Here, his early life was also important. County Tyrone is one of the six counties that make up Northern Ireland, in which the majority population is Protestant. John Hughes experienced being a Catholic in a Protestant area long before arriving in the United States.

RECOGNITION OF HIS ABILITY

John Hughes’s own entry into the priesthood was unusual, even for his time. The young man was never happy farming. Discerning a call to the priesthood, he went to the seminary at Mount St. Mary’s in Emmetsburg, Maryland. Lacking money, he could not go as a seminarian but did secure a job on campus as the gardener. He then begged and pleaded with the rector to be admitted to the school. The rector was John Dubois – whom John Hughes would later succeed as Bishop of New York. It took Hughes two years to be admitted – while also remaining the gardener.According to the book, Sons of Saint Patrick: A History of the Archbishops of New York, it was Saint Elizabeth Anne Seton – whose convent is adjacent to Mount St. Mary’s – who convinced Fr. Dubois to admit Hughes.

That little story points out another aspect of the representative character. While, as pointed out above, the representative character must be a product of the society – a part of the group – he must also have something that sets him apart. John Hughes’s parents sent him to school because they knew that their intelligent boy was different from their other children. Fr. Dubois and others in the Mount St. Mary’s faculty recognized his value. Bishop Henry Conwell of Philadelphia, who ordained John Hughes both deacon and priest, saw him as a protégé and sharpened his leadership abilities.

What does Saint Thomas Aquinas say about Marriage?

WISDOM AND PERSEVERENCE

There are other aspects of the representative character that he displayed. Such figures must have the quality of wisdom, an ability to see the current situation as it is and work within that situation. This is not the kind of petulance that one sees among the modern left – throwing a tantrum to force others to do what they want. This is hard work without guarantee of success. John Hughes had the virtues that came out of his Irish immigrant heritage, among them being the ability to convince, the willingness to work, the dogged perseverance, and the care of neighbor. At the same time, the vices that anti-immigrant America saw in the Irish were largely absent in him.

The representative character must be respected as a leader, and yet seen as a friend. When the word friend is used here, it is not in the sense that one might call a neighbor or working partner a friend. This is a more genuine quality of friendship – the willingness to fight for the groups’ interests.

By 1850, Archbishop Hughes was the most conspicuous Catholic in the United States, as well as being the most recognizable Irishman. Yet, he was not overawed by the new company that he was able to keep among the wealthy and powerful of the nation’s largest city. His was not a personality that would seek the approval of an intimidating Protestant establishment for personal acclaim. He used his access to the this establishment to fight for both Catholics and immigrants.

SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

Sometimes, he was successful. For decades, he fought against the anti-immigrant “Know Nothing” political party, which tried to make it impossible for Irish immigrants to become U.S. citizens. By the end of his life, the party became a mere footnote to American political history that it remains today. Other times he failed, as when he tried to get the taxpayers to support Catholic schools as they did for what he saw as the “Protestant” public schools.

Perhaps the best example of him as representative of the Church is his fight against what is called “trusteeism.” Canonically, Catholic parishes are the property of the diocese, the responsibility of the bishop. Typically, the seat of power in Protestant parishes is the laity. Therefore, they legally belonged to the lay trustees who in turn hired clergymen.

This use of trustees infiltrated into the Catholic parishes. It was favored by protestants who thought the idea of a “foreign priest” legally controlling real estate offended some Americans’ ideas of “the separation of church and state.” Some of those objecting were the lay trustees of Catholic parishes, who enjoyed the ability to control their priest.

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

This situation was intolerable to Archbishop Hughes as well as Pope Pius IX, a rigorous defender of the patrimony of the Church. The Archbishop had succeeded in carrying the day in two arenas. First, he convinced the New York State Legislature to pass laws allowing diocesan ownership of the real estate. This was no small task and involved working with politicians, most of whom were active anti-Catholics. The other arena was within the parishes themselves. He had to convince the trustees to turn over control to their bishop. This proved to be difficult. Most parishes eventually complied, but the Archbishop was forced to place an interdict on St Louis’s Church in Buffalo before they accepted diocesan control.

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

Perfection is not required of representative characters; they are, after all, fallen human creatures. Archbishop Hughes was not universally loved, and some of the complaints were justified. He was often viewed as belligerent. He seldom saw any value in an opinion that was not his own.

Perhaps the most important indicator of the representative character is that those who follow him know that they have a powerful and effective friend who can be trusted to look out for their interests. That was always true of John Joseph Hughes. That is the reason that he continues to cast a long shadow in the history of Catholic America, even though those who live in that shadow may not know the name of this exemplary representative character.

1. Bishop Coadjutor to the ailing Bishop John Dubois 1837-1842, Bishop of New York 1842-1850, Archbishop of New York 1850-1864.

2. Return to Order, p. 199.