Three hundred years ago, on May 25, 1720, the ship Grand Saint-Antoine docked in Marseille, France, coming from Syria. Due to negligence, laxity and corruption, the port and municipal authorities allowed an illegal passenger to disembark: the bacillus plague.

The events that followed are remembered in history under the name of “The Great Plague of Marseille.”1

1720: The Plague Devastates Marseille, a Rich but Vulnerable City

For two long years, the scourge punished the city and region. The highest estimates claim that about half of the population of Marseille succumbed to the plague. In the surrounding region of Provence, the population of 400,000 souls suffered between 90,000 and 120,000 deaths.2

On the eve of the epidemic, Marseille was the second or third largest city in France. It was governed by four municipal magistrates chosen by representatives of the city’s bourgeoisie.3

Despite France’s lagging economy, the city was prosperous. It was one of the largest ports on the Mediterranean and the largest in France. It enjoyed a quasi-monopoly on maritime trade with the Ottoman Empire, and particularly with the Levant (Near East) and the Barbary Coast (North Africa). In the eighteenth century, between two and four hundred ships from that region arrived in Marseille annually.4 In 1714, the value of products brought to the port from the Levant totaled a record twenty-three million English pounds.5

This intense traffic with the great Mediterranean ports made it more vulnerable to epidemics from the East than other ports. However, the plague had not reached Marseille for nearly seventy years due to a health system based on quarantine and lazarettos (enclosed areas) that prevented epidemics. When the security protocols were observed, the port and the city were relatively secure.6

Help Remove Jesus Bath Mat on Amazon

That long period of immunity contributed to a lack of vigilance that resulted in disaster.

Another Bacillus: the Jansenist Heresy

As often happens, times of great prosperity help create a spirit of moral laxity. Thus, the debauchery common to port areas overflowed to other parts of the city.

At the same time, another bacillus, more lethal than the biological plague’s carrier, infected the city in the form of Jansenism.7 This heresy infected sectors of the clergy, especially the Oratorians, who ran an important school. Some students were contaminated, as well as some convents and communities of women religious.

Jansenism introduced the theological and moral errors of Calvinism into the Catholic Church in France. The sect’s characteristics included rigorism, legalism, and scrupulosity. Among other things, its adherents denied papal primacy and infallibility. They claimed that Christ did not die for all men, but only for the predestined. They taught that the Sacraments should not be received often, but only after a long and severe preparation. Unfortunately, many people, under its influence, practically stopped receiving Our Lord at Communion.8

The Church repeatedly condemned these errors.

The Warnings of God and Men Fell on Deaf Ears

The plague did not come suddenly or unexpectedly. There had been no lack of warnings from men or God.

Satanic Christ Porn-blasphemy at Walmart — Sign Petition

As early as 1718, the great admiral of France, Louis-Alexandre de Bourbon, warned Sieur Le Bret, the governor of Provence, that the plague was hovering around Marseille. He prescribed a very precise quarantine, which was imposed on all ships coming from all infected countries.

Merchants from the Levant also alerted the Marseille authorities that the plague was raging in that region.

During the Forty Hours adoration before Lent in 1718, Our Lord showed Himself visibly in the Blessed Sacrament in the Church of the Friars Minor of Observance to the crowds gathered for worship.

“His face was so dazzling with majesty, his gaze both so tender and so severe that no one could bear the sight of it. The faithful assembled in the Church were terrified.”9

In the nearby Visitation monastery, Sister Anne-Madeleine Rémuzat simultaneously received a supernatural message that Heaven was angry with Marseille. She said that the Eucharistic prodigy was meant to convert the city. If Marseilles persisted in its sins, the city would be hit with a terrible punishment that would astonish all.

Sister Anne-Madeleine entrusted the Divine message to Fr. Milley, her spiritual director. He transmitted it to Bishop Henri de Belsunce.

Optimism, Carelessness, and Self-interest

Unfortunately, the carefree and frivolous city remained indifferent to the warnings of both men and God. The careless and optimistic authorities neglected the most basic safety standards to prevent the epidemic.

Despite its zealous bishop’s efforts, Marseille, once an example of religiosity, did not turn its back on immorality. Its clergy did not give up Jansenism.

How Panera’s Socialist Bread Ruined Company

Everything continued as before until…

“It’s the Plague!”

On May 25, 1720, the Grand Saint-Antoine docked in Marseille. It came from present-day Syria, where the plague was rampant. Her cargo was so infected that the crew fell ill. Nine sailors died during the voyage. However, the ship was not subjected to the strict confinement measures required by the health regulations. The ship owners, who were also city magistrates, feared that their precious cargo of Eastern fabrics would be damaged or lost if quarantined.

The negligent port doctors decided on a mild quarantine. After 15 days, the sailors disembarked and were locked in the quarantine hospital. The men did not bother to secure their dirty clothes, probably infested with fleas that carried the plague bacillus. They bundled them up and threw them over the enclosure to the washerwomen.

The cargo was stored in a warehouse where many people had access to it. They came into contact with the infected fabric.

On June 20, a washerwoman died after a few days of agony without anyone noticing the telltale boil on her lips. Only on July 9, after more deaths, two doctors finally sounded the alarm: “It’s the plague!”

However, the officials took no severe measures so as to avoid panic.

Until the beginning of July, these magistrates denied that the plague had infected people. They spoke of a “malignant fever” and still hoped that contagion would be limited. Only at the end of the month did they take effective action against the epidemic.

It was too late. The evil had already enveloped the city, sweeping through all its districts. It threatened neighboring provinces and the entire Kingdom of France. The scourge plagued the region for long months. At the height of the epidemic, from August 20 to September 15, a thousand people a day died in Marseille.

The plague epidemic advanced in the old city. Contagion first hit the poorest neighborhoods, where the sick and dead quickly multiplied.

Infirmary wards could no longer receive the sick. The old and dilapidated hospitals could not keep up with the demand for care.

On July 15, the bishop ordered all his priests to pray at Mass the prayer to Saint Roch, the great protector of Christians against contagion. He also exhorted the faithful to do penance.

A Horror Show

The symptoms of the disease were frightening. The unfortunate victims burned with fever and were covered with pustules. They died within a few days or even a few hours.

With the July heat, the city turned into a hell. Water was so scarce that the municipal councilors decreed that it be rationed. They threatened death to anyone who diverted water from the aqueduct for their use.

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

At first, the dead were buried in quicklime, and their houses were sealed. As the epidemic advanced, however, corpses were thrown onto the streets for lack of undertakers.

Those with the plague were left alone in their homes, with at most a piece of bread and a jug of water. The poorest had nowhere to turn for help. Many employed what little strength they had to drag themselves to the sanatorium. Many fell and died in the streets.

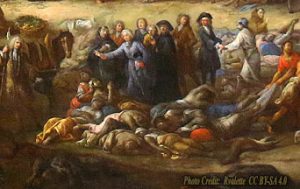

This description of the Provencal historiographer Jean-Pierre Papon, published in 1809, is impressive:

“This spectacle was particularly frightening in Dauphine Street, which is one hundred and eighty toises (360 yards) long by five (10 yards) wide. There, the bodies of the sick and dead were piled up to such a point that one could not take a step without stepping on them. This reason for this pile-up is that the street ended up at the hospital of convalescents.”10

As the situation went out of control, the bodies of the sick and dead invaded the streets:

“Whichever way you look, you see the streets all littered on both sides with piles of corpses, almost all rotten, hideous and appalling to see,” narrates Nicolas Pichatty de Crussainte, orator of the City Council and the King’s attorney in the police.11

Inspite of the streets being littered on both sides with piles of corpses, Bishop Henri de Belsunce, concerned with the eternal destiny of the victims’ souls, assumed the role of the Good Shepherd who gives his life for his sheep. “As for me, I intend to dwell with the plague-stricken, to console them, to die if necessary, of pestilence and hunger…”

“View of the Course during the plague of 1720” by Michel Serre, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille. Photo Credit: Rvalette, CC BY-SA 4.0.

By the end of August, Bishop Henri de Belsunce gave the following picture in a letter to the Bishop of Toulon:

“By the grace of God, I am still standing among the dead and dying. Everything around me was brought down, and of all the ministers of the Lord who have accompanied me, I have only one chaplain left. From my house, which has become a hospital for plague victims, eleven corpses came out, and I still have five people sick but out of danger … The plague has been in Marseille for three months and does not end. Alas! What have I not seen and felt, with two hundred dead bodies rotting around my house and under my windows for eight days! I was forced to walk the streets, all without exception, lined on both sides with half-rotten, dog-gnawed corpses, and the center strewed with throngs of plague victims and rubbish, so you did not know where to step. I had a sponge soaked in vinegar under my nose, my cassock rolled up under my arm, and had to cross vile corpses to find the dying, thrown out of their houses and placed among the dead on mattresses, to hear their confession and console them. Rotting heaps of slain dogs and cats increased the horror of the spectacle and the unbearable stench.”12

An Increasingly Terrifying Horror Show

On July 31, the parliament of Aix (capital of the province) established a sanitary cordon around Marseille and its territory. This isolated the unfortunate city from the rest of Provence and deprived it of feeding itself.

The parliament needed to take this severe measure to prevent the city magistrates from expelling two to three thousand hungry beggars. Their departure could spread the plague throughout the Kingdom. Marseille was thus left to its own devices.

To the disease were added hunger, unemployment, misery, robbery and looting. People were reduced to begging to feed themselves.

A deadly silence hung over the streets. Dead bodies filled the public places. The disease struck everyone, regardless of age, condition or rank. Fear seized people’s minds, and many fled the city for safety in the countryside. Among these were unfaithful civil servants.

The wealthy left Marseille to take refuge in their country villas. Authorities, civil servants and many priests took shelter in the fields.13

The monks of the famous Saint Victor Abbey took a cowardly attitude inside the city. They closed themselves behind the walls of their monastery and carefully sealed all openings. They contented themselves with sending alms and announced they were praying for everyone’s salvation.14

“The Terror Is Great, but I Trust in God’s Mercy”

In contrast to many religious and civil authorities, Bishop Henri de Belsunce assumed the role of the Good Shepherd who gives his life for his sheep. He refused to run for his safety.

“As for me, I intend to dwell with the plague-stricken, to console them, to die if necessary, of pestilence and hunger …”

He not only stayed in the city but went among the people. The only time he stayed away was for a few days in September when the stench of corpses accumulated in the streets and squares became unbearable. He could constantly be found dedicating himself to his sheep on the city streets and exposing himself to the plague through his contact with the sick.

Some priests were exhorted by their bishop and encouraged by his example to return to their posts. They heroically devoted themselves to giving spiritual assistance to the destitute.

The price was high: the vast majority of the secular clergy perished. Forty-three Capuchins, twenty-six Recollects, and eighteen Jesuits died, including Father Milley, confessor to Sister Anne-Madeleine Rémuzat. Soon only a handful of brave priests gathered around the bishop to assist the sick and give Last Rites. In his speech to the Assembly of the Clergy in 1725, Bishop de Belsunce declared that more than 250 priests and religious had perished in their mission of Christian charity.15

The churches remained open until the end of August. On August 24, Bishop de Belsunce was forced to close places of worship as corpses piled up at church doors. The magistrates systematically dumped them into church basements, where many had been buried at the beginning of the epidemic. The Bishop objected because he feared that the stench would infect the temples and render them unusable.16

With the closing of churches, some priests preached outdoors.

Bishop de Belsunce organized processions and collective prayers. The municipality banned them to prevent the spread of contagion.17

“I have just issued a reminder to order prayers and fasts, as the city councilmen asked me not to make a procession in imitation of Saint Charles [Borromeo] … The terror is great; however, I trust in the mercy of God.”

Bishop Henri de Belsunce was also concerned with the eternal destiny of the victims’ souls, particularly those who died without the sacraments and were buried in “profane soil.” Pope Clement XI sent two briefs granting a plenary indulgence to the faithful who died during the contagion when the priests celebrated the Mass of the Dead for them. On October 9, the bishop informed the secular and regular priests of his diocese about these “treasures of the Church.” He summoned them to free from purgatory the many thousands of souls for whom no one prayed.18

The Pope did not stop there. He sent two thousand loads of wheat from his Pontifical States to the people of Marseille.

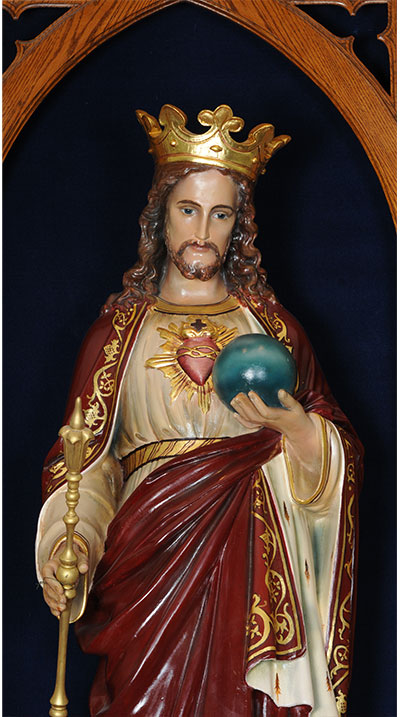

The “Safeguard” of the Sacred Heart of Jesus: a Powerful Spiritual Shield!

Faced with a lack of human resources to stop the scourge, Sister Anne-Madeleine turned to Heaven, asking how she might aid her helpless fellow citizens.

She received the inspiration that they should turn to the Heart of Jesus as the only one capable of helping them. Thus, at the urgings of Sister Anne-Madeleine Rémuzat, priests distributed thousands of Sacred Heart badges. On each one, the divine Heart was printed in black on a piece of white cloth sewn on top of red fabric. They had the inscription:

“Heart of Jesus, abyss of love and mercy, I place all my trust in Thee and hope for everything from Thy goodness.”

This call for confidence in Divine mercy directly opposed the Jansenist doctrines that infested the region. The Jansenist rejected all appeals to pity, piety or forgiveness.

The name badge was soon justified. This powerful spiritual badge protected thousands of people by preserving them from contagion or healing them after being infected.19

Examples of Heroic Courage: the Knight Nicolas Roze

Among those thus miraculously cured was the celebrated Knight Nicolas Roze, a man of faith and courage who is still revered as a hero.

When the plague broke out, Sir Nicholas Roze immediately offered his services to the city magistrates. Due to his administrative experience, he was appointed general commissioner for the district of Rive-Neuve. He closed the district and established checkpoints. He erected a gallows to stop looters, dug large pits to bury the corpses, and converted a rope factory into a hospital. He also organized the city’s supplies.

On September 16, 1720, Roze led a company of about 150 soldiers and convicts, the “crows,” equipped with tipping carts, tongs and rakes. They removed more than 1,200 corpses piled up for three weeks on the Esplanade de la Tourette in a poor neighborhood by the port. In half an hour, they put the bodies into pits and covered them with lime and soil. It was an extremely dangerous task: only 12 of the convicts were still alive five days later.

Roze tirelessly pursued his task until the plague hit him. His life was saved miraculously when he unexpectedly recovered.20

Military Intervention

On September 4, 1720, the Court appointed a military man endowed with extraordinary abilities to lead the city and its surrounding territory. The one chosen was Knight Charles Claude Andrault de Langeron, Commander of the Order of Malta, and Fleet Master in the royal galleys.

Langeron canceled social events of all kinds, closed or regulated markets, taverns, inns and houses of ill-repute. He enforced martial law and held absolute power in matters related to policing and city administration.21

A Bold Act: Consecrating the Diocese to the Sacred Heart

Bishop de Belsunce saw the epidemic as a punishment from God, primarily because of the Jansenists in his diocese.22

He organized several ceremonies to appease the Divine wrath: processions around the city, outdoor Masses under the porches of closed churches, and so forth.

However, after five months, the plague continued to devastate the city.

In her convent, Sister Anne-Madeleine offered her prayers and sacrifices and asked God to communicate to her what was missing from the public devotions. She communicated the reply to her superior. To show His mercy, God wanted the Sacred Heart of His Son to be honored.

Act of Reparation to the Sacred Heart of Jesus

“Having been ordered by my superior to ask God to let me know by what means He wants us to honor the Sacred Heart to obtain the cessation of the plague that afflicts this city, He let me know after Communion… that He was asking for a solemn feast to honor his Sacred Heart; that through prayer to the Sacred Heart, the people of Marseille would be delivered from contagion, and that finally, all those who adopt this devotion would only lack help when this Sacred Heart lacked power.”23

Bishop de Belsunce responded to this message with two initiatives. On October 22, 1720, he instituted the feast of the Sacred Heart in his diocese. On November 1, during a public ceremony, he consecrated the city and diocese to the Sacred Heart, an audacious and then unprecedented gesture. Once again, this move was a severe blow to the cold and cruel rigor of Jansenism.

As part of the consecration, the Bishop crossed Marseille barefoot, without a miter and with a rope around his neck to show that he took on himself all the city’s sins, as Saint Charles Borromeo had done during the plague in Milan in 1576. On the esplanade, he celebrated Mass and placed the diocese under the protection of the Sacred Heart. The terrible southern wind that blew that morning over the city paused only long enough for the ceremony. Bishop de Belsunce saw the pause as a sign of Divine blessing.

Immediately the plague diminished until it disappeared completely.

On June 20, 1721, the diocese of Marseille celebrated the Feast of the Sacred Heart for the first time.

The Sacred Heart of Jesus Wants to Be Honored Publicly and Officially

However, Heaven was not entirely satisfied. After the plague stopped, people returned to their promiscuity as often happens after periods of stress.

At the same time, some magistrates were imbued with Enlightenment skepticism or corrupted by Jansenism. These officials had failed to participate in the public consecration to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

In early May 1722, the epidemic reignited. Once again, the plague devastated the city and surrounding fields. It withdrew definitively only when the magistrates—as representatives of the public authority—officially involved the city in this devotion to the Sacred Heart.

Bishop Henri de Belsunce wrote Marseille’s magistrates:

“I do not want to offer you anything that could cause some expense to the city, unfortunately too badly tried. God does not ask for our gifts, but for our hearts. Therefore, in the name of the city, make a vow capable of disarming the avenging arm, which seems to rise again against us.”24

The municipal magistrates heard his appeal, and by the decision of May 28, 1722, hastened to promise:

“We, échevins of the city of Marseille, have unanimously agreed that we will make a firm, stable, and irrevocable vow in the hands of the Lord Bishop, by which, in said capacity, we commit ourselves and our successors, in perpetuity, to go every year, on the day when he has fixed the feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, to attend holy mass in the Church of the first monastery of the Visitation, known as the Grandes-Maries, to receive communion and, in reparation for the crimes committed in this city, offer a candle or torch of white wax, weighing four pounds, adorned with the coat of arms of the city, to burn this day before the Blessed Sacrament; to attend the same evening a general procession of thanksgiving that we pray and ask the Bishop to deign to establish in perpetuity.”25

Magistrates Moustier, Dieudé, and Pierre Rémuzat (Sister Anne-Madeleine’s uncle) pronounced the vow on June 4. They fulfilled it on June 12, the feast of the Sacred Heart.

From that day on, the number of sick people decreased wondrously. Public prayers were doubled. At the end of a novena promoted by the great bishop, the supernatural counteroffensive prevailed. The plague ended entirely.

Epilogue

After the plague ended, Bishop Henri François Xavier de Belsunce de Castelmoron became an object of great admiration and respect.

The King offered him the See of Laon. This appointment would make him Bishop-Duke, with both ecclesiastical and temporal jurisdiction, a great honor. Then the King offered him charge over the Metropolitan Cathedral of Bordeaux. Bishop Belsunce refused both offers and was content to accept the pallium sent by Pope Clement XII, as a mark of special favor.

He then declared:

“God forbid that I abandon a population of which I am obliged to be the father. I owe them my care and my life since I am their pastor.”26

He remained Bishop of Marseille for 45 years until his death in 1755.

Until his last breath, Bishop Belsunce fought against Jansenism.27

The Knight Nicolas Roze was appointed governor of Brignoles in 1723.

A widower, he remarried after the epidemic. He died on September 2, 1733.

Both Bishop Henri de Belsunce and Knight Nicolas Roze are honored with statues and have streets named after them.

Sister Anne-Madeleine Rémuzat was on her way to a higher honor, that of the altar.

She fell asleep in the Lord’s peace on the morning of February 15, 1730, at the age of 33. In Marseille, they said: “The saint has died.” Miracles were performed by invoking her intercession.

During the French Revolution, the enemies of the Sacred Heart—particularly Jansenists—destroyed all records of her heroic sanctity. Her process of beatification and canonization was severely disrupted by the damage to the documents.

However, at the request of the Most Rev. Joseph Robert, Bishop of Marseille, she was declared venerable by Pope Leo XIII on December 24, 1891, despite all the setbacks.

After several interruptions, her beatification process was reopened on February 15, 2014, by the Most Rev. Georges Pontier, Archbishop of Marseille. It was closed on July 2, 2015, and all postulation documents were filed in Rome on July 21, 2015, at the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints.28

Lessons for Our Days

In the present coronavirus epidemic, the “Great Plague of Marseille” of 1720 contains a great lesson for our days.

The plague of Marseille in 1720 contains a lesson of faith and trust in the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The spread of Sacred Heart badges brought relief and cures from the plague. The consecration of the city and the diocese, with the civil authorities’ participation, caused the plague to recede until it completely disappeared. Even today, after three centuries, the Mediterranean metropolis still celebrates its salvation through this devotion.

“This year, during the period of confinement caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the Archbishop of Marseille, Mgr. Jean-Marc Aveline anticipated the tercentenary of the consecration of the diocese to the Sacred Heart and solemnly renewed it on Palm Sunday, on the porch of [the church] Notre-Dame de la Garde.”29

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

Footnotes:

1. Michel Signoli and Stéfan Tzortzis, “La peste à Marseille et dans le sud-est de la France en 1720-1722: les épidémies d’Orient de retour en Europe,” Cahiers de la Méditerranée, p. 217-230, https://journals.openedition.org/cdlm/10903. Accessed 7/22/2020 3:29 PM.

2. Marseille City of Culture, “Great Plague of Marseille,” https://marseillecityofculture.eu/great-plague-marseille/. Accessed 7/26/2020 6:46 PM.

3. Fleur Beauvieux. “Épidémie, pouvoir municipal et transformation de l’espace urbain: la peste de 1720-1722 à Marseille,” Rives méditerranéennes, pp. 29-50, https://journals.openedition.org/rives/4177. Accessed 8/3/2020 12:44 PM.

4. Michel Signoli and Stéfan Tzortzis, “La peste à Marseille et dans le sud-est de la France en 1720-1722: les épidémies d’Orient de retour en Europe,” p. 217-230.

5. Wikipedia contributors, “Peste de Marseille (1720),” Wikipédia: L’encyclopédie libre, https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Peste_de_Marseille_(1720)&oldid=171623518. Accessed 7/20/2020 6:13 PM.

6. Fleur Beauvieux, et alii, “Marseille en quarantaine: la peste de 1720,” L’Histoire, April 17, 2020, https://www.lhistoire.fr/marseille-en-quarantaine%C2%A0-la-peste-de-1720. Accessed 7/25/2020 5:40 PM.

7. Father Dehon, Mois du Sacré-Cœur de Jésus, (Paris: Librairie René Haton), p. 87, http://dehondocsoriginals.org/pdf/OSP-MSC-0001-0004-8060104.pdf.

8. See Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, “A First Milestone in the Rise of the Counter-Revolution.” December 5, 2008, https://www.tfp.org/a-first-milestone-in-the-rise-of-the-counter-revolution/.

9. Armand Praviel, Belsunce et la peste de Marseille (1936), pp. 199-200.

10. Apud François Cau, “1720: la peste dévaste Marseille,” Retronews, May 24, 2018 (updated 3/16/2020), https://www.retronews.fr/sante/long-format/2018/05/24/1720-la-peste-devaste-marseille?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI8bTF4Y_m6gIVD6_ICh2maAipEAMYASAAEgLarvD_BwE. Accessed 7/24/2020 11:28 AM.

11. Fleur Beauvieux, “Marseille en quarantaine: la peste de 1720.”

12. Dom Th. Bérengier, O.S.B., Mgr. de Belsunce et la peste de Marseille (Paris: Librairie de la Société Bibliographique, 1879), pp. 26-7.

13. Wikipedia contributors, “Peste de Marseille (1720).”

14. Wikipedia contributors, “Abbaye Saint-Victor de Marseille,” Wikipédia, https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbaye_Saint-Victor_de_Marseille#La_sécularisation_au_Grand_siècle. Accessed 7/30/2020 5:00 PM.

15. Joseph Sollier, “Henri François Xavier de Belsunce de Castelmoron,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907), http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02425c.htm. Accessed 7/21/2020.

16. Régis Bertrand, “La peste de 1720-1722 à Marseille: 1. Sauver des âmes en temps d’épidémie, Garrigues et Sentiers, May 27, 2020, http://www.garriguesetsentiers.org/2020/04/la-peste-de-1720-1722-a-marseille-1.sauver-des-ames-en-temps-d-epidemie.html. Accessed 7/22/2020 4:18 PM.

17. Fleur Beauvieux, “Marseille en quarantaine: la peste de 1720.”

18. Régis Bertrand, “La peste de 1720-1722 à Marseille: 2. À qui se vouer?,” Garrigues et Sentiers, May 27, 2020, http://www.garriguesetsentiers.org/-84. Accessed 7/22/2020 4:18 PM.

19. “VII. Les Images du Cœur de Jésus – I. Les Sauvegardes,” Perles de la Dévotion au Cœur de Jésus: Les Images. (1902), https://francais-et-chretiens.home.blog/tag/soeur-anne-madeleine-remusat/. Accessed 7/31/2020 9:37 PM.

20. Ministry of Culture, “Hôpital Caroline (Iles du Frioul),” Le Parisien, September 16, 2018, http://marseille.aujourdhui.fr/etudiant/sortie/jep-ouverture-exceptionnelle-de-l-hopital-caroline-journees-du-patrimoine-2018/imprimer/flyerRecto.html. Accessed 7/31/2020 3:37 PM.

21. Cindy Ermus, “The Plague of Provence: Early Advances in the Centralization of Crisis Management,” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2015), no. 9, Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7029.

22. H. Carré, Le règne de Louis XV (1715-1774), vol. VIII, part II of Henry E. Bourne’s, Histoire de France depuis les Origines jusqu’à la Révolution, published under the direction of M. Ernest Lavisse, (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1909), p. 62, note 1.

23. Mgr Jean-Pierre Ellul, “Notes sur La Vénérable Anne-Madeleine Rémuzat,” February 21, 2006, http://mgrellul.over-blog.com/article-1864820.html. Accessed 7/20/2020.

24. Bérengier, Mgr. de Belsunce et la peste de Marseille, pp. 26-7.

25. Ibid.

26. “François-Xavier de Belsunce de Castelmoro,” Wikipédia, https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/François-Xavier_de_Belsunce_de_Castelmoron. Accessed 7/20/2020 5:39 PM.

27. Joseph Sollier, “Henri François Xavier de Belsunce de Castelmoron,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907), http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02425c.htm. Accessed 7/21/2020. “François-Xavier de Belsunce de Castelmoro,” Wikipédia, https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/François-Xavier_de_Belsunce_de_Castelmoron. Accessed 7/20/2020 5:39 PM.

28. Anne-Madeleine Remuzat contributors, “Portrait d’Anne-Madeleine Rémuzat,” March 30, 2011, http://annemadeleineremuzat.over-blog.fr/article-portrait-d-anne-madeleine-remuzat-70559818.html. Accessed 7/21/2020 11:41 AM.

29. Régis Bertrand, “La peste de 1720-1722 à Marseille – 2. À qui se vouer?,” Garrigues et Sentiers, May 27, 2020, http://www.garriguesetsentiers.org/-84. Accessed 7/22/2020 4:18 PM.